By John Kaverman, president, Pad Print Pros

Most technical information from pad printing ink manufacturers will say something like, “Thinner is added to the ink to adjust the printing viscosity,” with text following that usually is accompanied by a range of, for example, “10% – 20% by weight.” In my opinion, the use of the word “viscosity” is misleading, because it is the evaporation rate that determines if the ink efficiently will transfer, first from the cliché to the transfer pad and then from the transfer pad to the substrate.

Viscosity refers to a substance’s resistance to flow – in essence, how fluid it is. A substance with a low viscosity will have very little resistance to flow (think water). Accordingly, a substance with a high viscosity will have a stronger resistance to flow (think honey).

The problem with trying to define a specific viscosity for a specific pad printing ink stems from the fact that two different batches of the exact same ink and color, having the same viscosity but different evaporation rates for the thinners used to achieve that viscosity, can have vastly different transfer efficiencies.

The evaporation rate, or “speed,” of the thinners used to achieve the viscosity is more important than the viscosity itself.

Why? In a perfect world, applications would be printing the same ink, in the same color, on the same parts while using the same artwork (image), the same type of cliché with the same etch characteristics (depth, line screen frequency), the same transfer pads in the same shore (hardness) and the same machine parameters in a climate-controlled environment. But those applications are extremely rare.

Successful pad printing requires that each of the variables mentioned in the previous paragraph be as defined and controlled as possible. That’s why I’ve been preaching that “pad printing is a science, not an art” (which, coincidentally is the title of my latest book about the process) for the past 25 years. Let’s look more closely at those variables.

Pad Printing Inks

It is a fact that inks of a different color but of the same exact series have different viscosities when the can is opened. That’s why, most of the time, pad printing inks are packaged by weight and not by volume. It also is why the instructions for mixing ink with catalyst and thinner state percentages by weight and not by volume. As a result, different colors will require different percentages of thinner by volume to maximize their respective transfer efficiencies.

Artwork (Image Characteristics)

Ink dries inward from the outside edges of the printed film. This happens on the cliché prior to the pad picking the image up once the ink is on the transfer pad and again after the ink is transferred to the substrate. That means that fine lines and tiny details dry faster than bold areas and large, solid areas of coverage.

Anyone who has ever been tasked with printing a tiny trademark or copyright next to a bold corporate logo in the same hit knows what I am talking about. The trick is to thin the ink to maintain the transfer efficiency of the tiny trademark, while not going so far as to jeopardize the transfer efficiency of the bolder part of the image. This requires compromise and then some other things downstream in the process to compensate.

Cliché Plates

There are numerous types of clichés (photopolymer, thin steel, thick steel, laser-engraved), with different etch depths and different etch profile characteristics (straight etched, screened, etc.). Some types of clichés and etch profiles are better suited than others in specific applications, and the control of the variables involved in manufacturing then needs to be controlled to maintain consistency when, for example, printing hundreds of thousands or millions of the same product and replacing clichés on a regular basis.

When it comes to adjusting ink as it relates to cliché plates, deeper clichés equal more ink volume, which equals slower drying on the cliché prior to pick-up and on the pad in between pick-up and transfer. So, to maintain ink transfer efficiency with a deeper cliché, a lower percentage of thinner by volume (or a faster evaporating thinner) is needed. If the cliché has a shallower etch depth, compensate by adding more thinner by volume (or a slower evaporating thinner).

What constitutes an unacceptable variation in etch depth? For a standard, solvent-based pad printing ink, the range of depth for a straight etched cliché is between 18 and 27 microns. Variation of +/- 3 microns is typical within that range. Certain applications, such as those run at high speed (30+ cycles per minute), typically will be shallower, as will clichés for UV-curable inks.

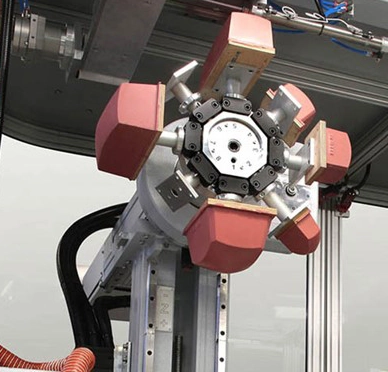

Transfer Pads

Different grades of silicone materials are used in manufacturing transfer pads. The amount of silicone oil in the formulation dictates the hardness (shore/durometer) of the pad, and the type of mold used affects the pad’s surface characteristics (shiny or matte). Pads of the same shape but of a different shore (hardness) transfer different ink film thicknesses. For example, if comparing the ink film thickness transferred using a softer three shore (A scale) transfer pad and harder nine shore pad, the softer pad transfers more ink than the harder one.

When it comes to adjusting ink as it relates to transfer pads, the same ink, once residing on the transfer pad after being picked up from the cliché, will dry faster on a hard pad than on a softer pad.

Machine Cycle Parameters

There are six steps to any pad printing cycle, regardless of whether the cycle is 0.2 seconds (18,000 parts per hour), two seconds (1,800 parts per hour) or 20 seconds (180 parts per minute).

If the machine parameters cannot be adjusted for speed, as in the case of automated systems that are printing inline and therefore at the same rate as related production equipment, then the consistency of the ink (and control of the other variables previously mentioned) becomes more important. When there is the latitude to independently adjust the speeds of the printing equipment’s axes of motion and/or program delays at the ends of those axes of motion, the consistency of the ink is less important.

Production Environment

Temperature and relative humidity have an impact on pad printing. For this reason, it is preferable to print in a climate-controlled environment. Yes, it’s possible to print in an uncontrolled warehouse in Texas in the middle of August… but I can guarantee it will not be fun.

Most inks and solvents are petrochemicals and, being made from petroleum distillates, they don’t like water. While variations in temperature impact ink transfer efficiency, variations in relative humidity have a larger impact. When humidity is low, the air is drier, and evaporation happens more quickly. When humidity is high, the opposite occurs. When humidity is 100%, evaporation basically stops… and printing becomes a huge problem.

How much of a problem? Well, Willis Carrier, the American engineer who invented air conditioning in 1902, invented air conditioning in response to a humidity problem at a printing company. That’s right… Air conditioning was invented to control the environment for printing, and not so we all can be comfortable in our homes, cars and hermetically sealed offices.

Hints for Thinning Pad Printing Inks

At this point, it’s reasonable to say, “Why in the world would anyone pad print? It seems complicated.” It is and, at the same time, it is not.

Figure 1 illustrates what I was talking about when I referred to evaporation rates. The Y axis is relative humidity. The X axis is ambient temperature. The three squares represent lower (red), middle of the road or “average” (yellow) and high (blue) conditions of temperature and relative humidity. Consider the yellow conditions to be pad printing’s “happy place,” with optimal conditions being 68o to 72o F and relative humidity of 55% (+/- 10%).

Now, further consider that when looking at the technical data sheet for most pad printing inks, there will be a choice of thinners. Typically, there are at least three, usually referred to in terms of their respective evaporation rates: slow, medium and fast. In the graphic, the yellow zone is where a thinner with a medium evaporation rate will be used, the red zone is where a thinner with a fast evaporation rate will be used and the blue zone is where a thinner with a slow evaporation rate will be used. Where the colored boxes overlap in the graphic, it might be necessary to blend medium with fast (orange area), or medium with slow (greenish area).

How much of which thinner initially is used in any of the zones illustrated in Figure 1 will vary. Again, this goes back to different colors of the same ink, cliché depths, transfer pad hardness and machine parameters.

Assuming that I am working a “yellow zone” kind of environment (and I know that my clichés and pads are correct), I start at the lower end of the ink manufacturer’s recommended range, with 10% medium-speed thinner in darker colors and perhaps 12% in lighter colors. This is because lighter colors of ink usually have a higher specific gravity (weight by volume) than darker colors. They are thicker, so they need more thinner to begin with.

I always start by printing something (scrap parts) 10 to 15 times to wet everything up. Ink acts like a lubricant on the cliché while it is sloshing around in the ink cup during the doctoring process. The more it moves, the more fluid it typically becomes (like when stirring stuff in the kitchen). The introduction of thinner to the silicone pad also increases the pad’s ability to efficiently pick up and transfer the ink as the pad slightly swells on the surface where the image is. After 10 to 15 cycles, I clean the pad and print a part for evaluation of image quality. I recommend never evaluating the first few parts off the machine for image quality. Until everything gets moving, adjusting the ink is a mistake.

Now, look at that dotted line diagonally going across the red, yellow and blue zones in Figure 1. That is a representation of the increase in the percentage of thinner as temperature and humidity increase.

If the ink is drying too quickly (for example, I am printing bold areas but not fine lines), I will add more medium thinner… perhaps 1% to 2%. If the ink already is too wet (and not partially transferring to the substrate, but with a lot remaining on the pad), it indicates that I need to either slow down one of the machine strokes (pad up at pick-up and/or pad down at transfer), program in a delay prior to transfer (in perhaps 0.5 second increments) until it completely transfers or (if I don’t have the latitude to slow down) direct some air at the image area of the pad in between image pick-up and transfer to accelerate the evaporation of the thinner from the ink film.

If I am in the blue zone (because it is a hot, humid day) and I am working with a medium-speed thinner, I might get to a point where I’ve added thinner and am nearing the top end of the manufacturer’s recommend range. Then the image usually starts looking washed out (not opaque). At that point, I essentially am no longer transferring enough solids (pigment). I’ve thinned the ink as far as I can using medium-speed thinner, and the results are not acceptable.

In this case, I would stop, mix new ink and blend slow thinner (commonly referred to as “retarder”) with medium-speed thinner, starting with one part retarder to three parts medium-speed thinner, and try again. By adding some retarder, I am slowing the ink’s drying speed down while keeping the viscosity of the ink within a range where it transfers and provides acceptable coverage (opacity) and image quality.

At the other end of the spectrum, if I were printing when it was cold and dry, and I have tried using less than 10% medium-speed thinner, but the ink still is too wet and won’t release from the pad, I stop. I now am in the red zone and need to mix up a new batch of ink, this time blending fast with medium, starting with a ratio of one part fast to three parts medium thinner.

Summary

This might seem like a lot of confusing, time-consuming nonsense, but to be successful with pad printing and not frustrated every time the printing environment or some other variable decides to pop up, it’s necessary to learn.

I started out in pad printing after having been a screen printer for nine years, and it took me a while to figure it out. The trick is keeping track of where the process is, so it’s easier to figure out which direction to go to maximize ink transfer efficiency. Weigh inks and additives as the formulations are being mixed for different inks, colors and artwork types (fine details vs. bold images, combinations of fine and bold). If not fortunate enough to work in a climate-controlled environment, buy a digital thermometer/hydrometer and put it in the production area to record those variables along with the respective thinner percentages or blends. Over time, will be gathered data that can be put into an “ink mix matrix” for quick, visual reference indicating where to start with certain inks under varying conditions.

Remember, pad printing is a science, not an art.

John Kaverman is president of Pad Print Pros, an independent sales and consulting firm specializing in plastics decorating technologies, with a focus on pad printing. A graduate of Ferris State University (Michigan) with a degree in Printing Technology, Kaverman has 35+ years of industry specific experience.

For more information, email padprintpro@gmail.com or visit www.padprintpros.com.